The Most Important Filmmaker You’ve Never Heard Of: Rouben Mamoulian, Part 1

A Case for Mamoulian as a Preeminent Figure of Pure Cinema

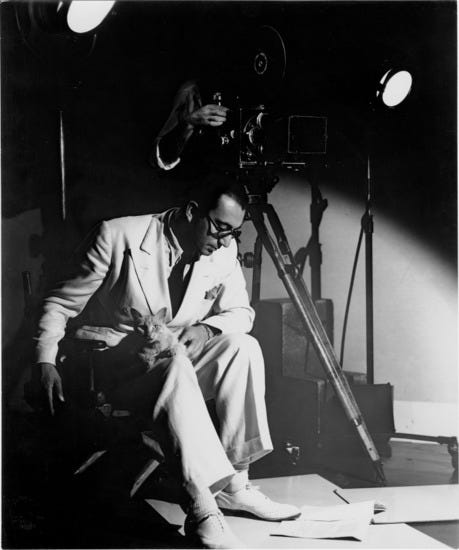

The most famous quote about Tblisi-born filmmaker Rouben Mamoulian, a name not often thrown around in contemporary cinephilia, is a bittersweet one. It comes from Andrew Sarris’ seminal book, The American Cinema, where the critic called him “an innovator who ran out of innovations” and placed him in his proprietary category Less Than Meets the Eye. The quote refers to the many techniques that Mamoulian introduced to cinema, including overlapping sound, subjective sound and camera and non-realistic sound, as well as making the debut three-strip Technicolor production, Becky Sharp (1935).

Since then, he’s largely been considered under such a designation, in terms that distill his artistry down to that of a technician, while also, as Tom Milne notes in his quite good if occasionally overstated 1969 monograph, makes for complete neglect of Mamoulian’s later films.

Of course, there have been reevaluations of Mamoulian’s work along the way, including, most recently, a couple skeptical pieces in 2007 from Dan Callahan in The House Next Door and Adrian Danks in Senses of Cinema, a 2016 Harvard Film Archive series called “Rouben Mamoulian, Reconsidered” and just last year, Il Cinema Ritrovatro did a retrospective of the majority of his work, after which, attending critic Jessica Kiang contended that seeing just five of the films on offer “were enough to convince any skeptic of the director’s right to a plinth in the Hollywood pantheon.” Harvard’s Haden Guest goes further, “Easily equal to great studio directors such as King Vidor, Tay Garnett or early Mervyn LeRoy, Mamoulian at times reached that ineffable level of his greatest fellow émigré artists — Murnau, Lang, Hitchcock.”

Regardless of where his reputation goes from here, it should be noted that Mamoulian isn’t some early cinema version of style over substance; he’s a filmmaker who thought about the medium in a new way. He considered film a “man-made miracle” and approached it as such. “The camera fascinated me,” he’s quoted as saying. “Some theorists talk about the camera as a means of rendering reality. This is true; but the camera’s greater and more glorious power is in its capacity of conveying truth through stylization and poetic rhythm.” For him, style was the avenue to substance.

Mamoulian was brought to Hollywood under the assumption that his roots in theater would transfer something theatrical to the cinema. When asked, during a chat at North Carolina State University in 1977 (printed in a 1982 issue of Film Quarterly), what he brought to cinema from theater, Mamoulian replied, “I didn't bring any ideas from the theater because I don't think theater can give any ideas to the films. They are different mediums. There is nothing really in the theater that can contribute to films.”

In International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers, Patricia King Hanson said Mamoulian isn’t “considered strictly an auteur with a unifying theme running through his films,” even if his place in film history is significant. At the time of this post, I’ve only seen six of his 16 features (and his uncredited first work, The Flute of Krishna, which played at this year’s Nitrate Picture Show), so I’m not in a position to debate the categorization. However, if there is a theme that runs through his work, it’s something along the lines of “doubling” — opposing forces, often within one entity, or a performance vs. its non-performance. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) is the most obvious articulation of this theme, but it’s writ both small and large elsewhere, be it the country vs. city in Applause (1929), the dangerous world within the unassuming “beer industry” in City Streets (1931), Maurice Chevalier’s tailor-as-baron in Love Me Tonight (1932), Gene Tierney’s shopgirl-as-millionaire in Rings on Her Fingers (1942) or, most poignantly, Marlene Dietrich’s Russian Doll-like performance in The Song of Songs (1933).

This is the first in a series of pieces about the works of Mamoulian’s films wherein I will further examining the fabrics of films from an artist I consider a preeminent figure of pure cinema.

Applause (1929)

In his intro, Milne says it's tempting to call every Mamoulian film a musical, “It isn’t true, of course, but with every action and every line of dialogue conceived in terms of stylised rhythm – choreographed rather than directed – it feels as though it were.” Il Cinema Ritrovato programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht echoed that, “In a sense, his films brought some of Sergei Eisenstein’s ideas to the idiom of musical film, even if only less than half of his films were actually musicals.”

His debut film, Applause, has been referred to as a “backstage musical” since much of it captures the lives of performers on and off the stage, but as happens with Mamoulian films, the literal musical elements come and go, often without strict genre adherence.

I went into Applause not knowing I would end up writing about Mamoulian’s work, assuming it, a relatively unknown debut film from a relatively obscure filmmaker, was a rough, minor work with hopefully more than little intrigue. But the filmmaker immediately announces himself as a talent.

The film opens on a tracking shot that begins on a shop sign pulls back to a deserted street where crumpled signage blows like tumbleweed until the street slowly fills with people running toward the sound of live music. Once inside the burlesque show, the film pivots around the band. Mamoulian roams over each performer during an unbroken, roaming tracking shot of closeups.

Not only is there a sophisticated rhythm to the movement and editing of the film’s opening minutes, but there’s a fascination with the image in a way only cinema can create. As Milne notes, “The very opening sequence indicates that Mamoulian was thinking in terms of movement rather than sound, and in terms of cinema rather than theatre.”

Applause is known to film historians primarily for its use of overlapping sound, but besides its routinely shocking and modern aesthetic flourishes, which the film deserves more credit for, I’ll remember it more often for its natural location photography. Apparently, Mamoulian was interested in the film because he was interested in New York, which he referred to as a “garbage dump,” but “even in a garbage dump, a beautiful flower can grow,” he said.

Funny enough, shooting exteriors was illegal in 1928. “So naturally, I wanted to photograph New York,” said Mamoulian, prefacing a humorous story of early guerilla-style filmmaking:

So I found a very simple way. We engaged 400 extras to shoot at the Pennsylvania Station where the daughter arrives from a convent to see her mother in New York. And I said, "Well, we'll go to the Pennsylvania Station, and we will all be passengers. We'll have suitcases, and we'll be coming out of the station, and we'll call taxis; get in." And I said, "We will have hidden cameras," and I said, "If the first take isn't any good, I'll wave my white handkerchief, and all of you go back and do the whole thing over again and call the taxi." So there we were, and they came out, and the taxi's coming down, and they all started going into action. I wanted a second take so I waved my handkerchief, and suddenly the whole crowd got out of taxis and went back into the station, and you should have seen the faces of the taxi drivers! You know, they thought they were going crazy! Everybody suddenly giving up the taxis. And then we came back again hiring them. Well, anyway that was breaking the law, but I feel the statute of limitations is over, and they can't arrest me now.

This is just one of the ways he went beyond the law for the film’s exterior shots. One of the most memorable sequences is a love scene between a sailor and a girl on top of a skyscraper:

At the end of this scene, you see, they fall in love with each other, and at the end of the scene I wanted an additional lift. And I felt that if an airplane came by and swooped rather low over this scene that this would give a kind of a lift to the whole thing. So I engaged a pilot, and he said he would do it on a certain cue, and sure enough down came this plane. Of course, all the police stations started calling each other, I was told later, because that was breaking the law. It seems that he flew too low for the rules of New York.

Mamoulian’s reason for creating this scene: “So very frequently I can see seemingly irrelevant images could add greatly to the emotional value of a scene.” Again, it’s very funny that this is the man Hollywood wanted for his theater background — a man who clearly saw film as a medium of artistic opportunity.

William K. Everson (in American Silent Film), who says the film is slightly less than successful, calls it as important a film in 1929 as Citizen Kane was in 1941. He basically says Mamoulian was ahead of his time, reporting that some of his ideas for Applause, “especially some involved moving camera shots, were sabotaged by crews that wanted to put this upstart in his place and prove to him that what he asked for couldn’t be done.”

According to a 1967 New York Film Festival program note, the film’s 35mm negative was lost for years. While I agree with Everson that not everything is wholly successful, primarily the drama, one wonders if the film would have a much better reputation if it had been seen more frequently in the intervening years.

City Streets (1931)

Mamoulian’s sophomore effort, City Streets, is a super cool gangster film made during the genre’s heyday. As Milne notes, the film hews closer to Josef von Sternberg’s early gangster work than the contemporaneous films James Cagney was making a name from. “Lowering shadows and looming statuary…are to him what fishnets and feathers were to Sternberg” goes a memorable line from Milne.

In the aforementioned 1977 interview, Mamoulian talks explicitly about fighting with the cameraman on lighting for shadows. The cameraman would contend that the producers are paying “to see it all.” I have no idea if he had less of a fight to put up on City Streets or not, but this is where that visual language starts to find its cohesion.

The film’s drama is carried by two memorable performances from do-gooder Gary Cooper and Sylvia Sidney, the latter of which unwittingly gets the former caught up in her mobster father’s ugly business. As he does in an even more naive role in Howard Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941) a decade later, Cooper is so good at telegraphing his moral compass and having to struggle with it for the first time in his life.

Tangentially, seeing more of Cooper’s early roles makes me further appreciate how Leo McCarrey uses him in Good Sam (1948), which is playing off this do-gooder reputation, and impulse, that Sam can’t outrun. Of course, Anthony Mann would further complicate this a decade later during his prime run of dark and cynical westerns with Man of the West (1958).

Cooper’s performance in City Streets, his makeup, posture and facial expressions, feels stuck in a silent film. It’s perhaps a microcosm of what’s so unique about Mamoulian’s early works — this feeling of not only being caught between the silent era and the talkies, but of being so technically and technologically ahead of so many of his peers in the sound era (von Sternberg excepted).

Expounding on this, recalling the pivotal early scene that sends Sidney’s Nan to jail, Milne says, “The whole sequence is a brilliant, almost bravura display of pure cinema which leaves one in no doubt that Mamoulian knew and had thoroughly absorbed the techniques of the silent film.” He goes on to describe his dialogue “almost like stress marks, indicating the accents in a verse where the poetry is carried by the images, the rhymes by the editing and camera movements.”

That understanding of image-forward storytelling makes it even more remarkable that Mamoulian is more known for his innovations in sound, this film included. In City Streets, Mamoulian uses subjective sound during a close-up of Nan in her jail cell. The sound overlaid comes from those in her thoughts, including Cooper’s The Kid. It’s a moment that feels natural now, a primary tool adopted into our visual language. But the temperature was quite different in 1931, according to Mamoulian:

I first did it in City Streets and everybody told me that it was misleading- people won't understand how come you see a close shot of Sylvia Sidney. She is not moving her lips, and yet you hear her talking to Gary Cooper. And I said, "Well, you know that she is reminiscing and thinking." They always underrate audiences. So we shot it anyway, and of course at the preview everybody knew what it was. I did something you can't do on the stage but you can do on film. And today there is hardly a film that doesn't use that device.

Like with Applause, the drama in City Streets is a bit thin, although buoyed here by its central star performances, both of which peak during a scene when The Kid visits Nan in jail. They share a passionate moment separated only by the netted window — a scene that, as Ethan Vestby notes, anticipates the one in Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket (1959) that Paul Schrader has made his life’s mission to recreate.